Bhāratīya Education (Part – 2)

Nearly every village was found to have at least one school.

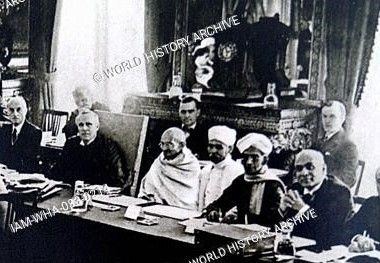

“You Have Uprooted Our Education System”: Mahatma Gandhi to the British

Historian Dharampal got involved in the Quit India Movement as a young boy and was a strong adherent of Gandhian philosophy. He read Mahatma Gandhi’s long address at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House that was made on 20 October 1931 in which Gandhi stated the following:

...That does not finish the picture. We have the education of this future state. I say without fear of my figures being challenged successfully, that today India is more illiterate than it was fifty or a hundred years ago, and so is Burma, because the British administrators, when they came to India, instead of taking hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They scratched the soil and began to look at the root, and left the root like that, and the beautiful tree perished. The village schools were not good enough for the British administrator, so he came out with his programme. Every school must have so much paraphernalia, building, and so forth. Well, there were no such schools at all. There are statistics left by a British administrator which show that, in places where they have carried out a survey, ancient schools have gone by the board, because there was no recognition for these schools, and the schools established after the European pattern were too expensive for the people, and therefore they could not possibly overtake the thing. I defy anybody to fulfill a programme of compulsory primary education of these masses inside of a century. This very poor country of mine is ill able to sustain such an expensive method of education. Our state would revive the old village schoolmaster and dot every village with a school both for boys and girls.

Further, Gandhi pursued the questioning of Sir Philip Hartog thus at Segaon in August 1939:

...I have not left off the pursuit of the subject of education in the villages during the pre-British period. I am in correspondence with several educationists. Those who have replied do support my view but do not produce authority that would be accepted as proof. My prejudice or presentiment still makes me cling to the statement I made at Chatham House. I don’t want to write haltingly in Harijan. You don’t want me merely to say that the proof I had in mind has been challenged by you!

Gandhi’s inability to provide proof to the British authorities made the British appear to be in the clear and this placed the education system in the nation at a disadvantage. The conviction of Gandhi’s words prompted Dharampal to explore and get hold of authority that would be accepted as proof. His exploration resulted in the publication of the book ‘The Beautiful Tree’* – obviously alluding to the tree that Gandhi mentioned as being laid to waste – in 1983.

With perseverance, he accumulated not merely the documents that would have provided proof to officers like Hartog but a lot more that gave much insight into how the Britishers viewed the Indian education system before they introduced their education pattern. Dharampal gained access to the documents that were made by the British officers, surveyors and administrators. He has also quoted evidences from the published works of Britishers who were associated with the East India Company prior to 1858 and to the British Crown after that until India gained freedom from British rule. Some extracts from the book are given below.

The British had conducted extensive surveys in various provinces including Bengal, Punjab and Madras on the number of schools, how many students went to these schools, the demographics of the students in the schools, the curriculum taught at school, the methods used for teaching and so on. Most of what they learnt shook the assumed superiority of British to their foundation.

Nearly every village was found to have at least one school. Close to 100 percent of the village male children went to this school. Rarely, there were some girls also. Girls had their education at home from their parents or a tutor. Similarly, the children of the more affluent people engaged private tutors for their children.

Schools of Pathasalas were conducted in a variety of settings – sometimes at the homes of the students, sometimes at a wealthy person’s home or under a tree or some sheltered thatch. Every school consisted of a teacher and his students numbering less than twenty. The students began education anywhere between the ages of 5 and 8 and completed their schooling by 12 to 14 years of age. After this they pursued their family trades or went to colleges gurukulas for higher studies. Since the concept of school did not involve any sort of infrastructure, it was quite tedious for the British to manage the data collection in an accurate manner.

The children learnt writing, reading, the arithmetic operations and rules of taxes and such practically applicable things. They had to study the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas. Children going to Islamic schools studied the Kuran.

Contrary to what we are made to believe, a very high percentage of the schools across the country had more children from Shudra castes (between 40 to 65%) while the percentage of Brahmin children was small (less than 15%). This corresponded well to the population percentages. Except for the Harijans, all the other children went to school together. These schools continued to function for decades after the schools following the Macaulayan pattern began being established.

John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow in his book British India (Vol 1) says:

“In every Hindoo village which has retained anything of its form, I am assured that the rudiments of knowledge are sought to be imparted; that there is not a child, except those of the outcasts (who form no part of the community), who is not able to read, to write, to cipher; in the last branch of learning they are confessedly most proficient.”

So, when the schools were obviously doing a good job, why did the British want to establish a new system of education in India?

What is the answer to the fair question posed by Ludlow even in those days?

(Will continue in the next part)

References:

Dharampal (2000). The Beautiful Tree, Other India Press. Available at: http://www.arvindguptatoys.com/arvindgupta/beautifultree.pdf

Ludlow, John Malcolm Forbes (1858). British India Vol 1, Macmillan and Co. Available at: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.195586/page/n1/mode/2up