Looking at Our Festivals through the Pañcāṅgam Lens

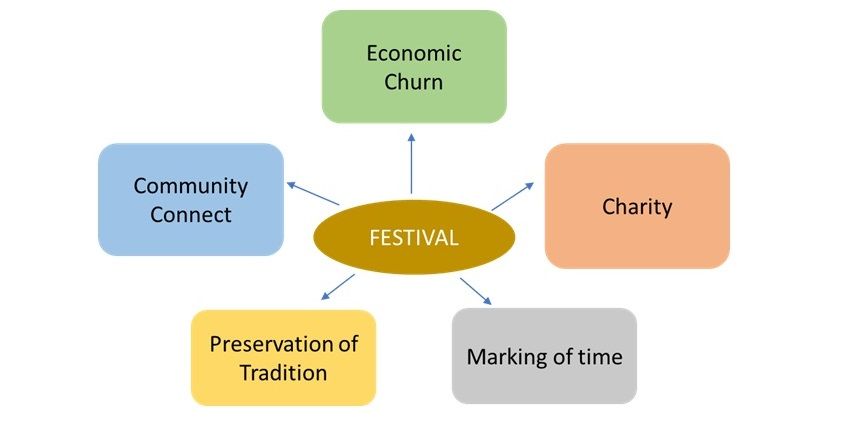

The desire to enjoy life beyond the mundane is built into the nature of man. Thus, we find that man takes pleasure in expressing joyful emotions and performing joyful actions to connect with others and with nature. When the expression becomes collective and includes all members in a community, then it becomes a festival. So, by definition, a festival is meant to be celebrated beyond the boundaries of the individual and the family/home.

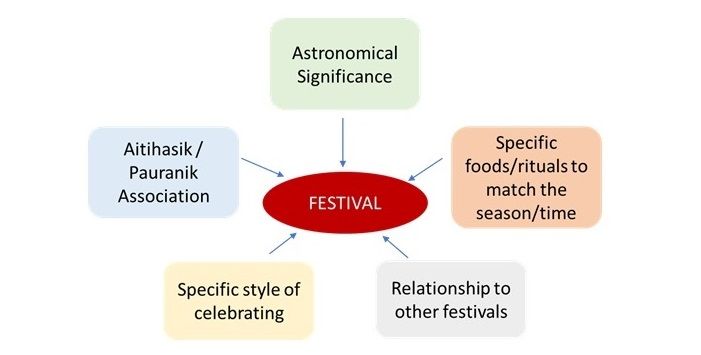

The earliest reasons for observing festivals can be guessed to have been the arrival of specific seasons, availability of food in abundance or some such favourable situations. As human societies evolved over time, they began celebrating events of historical significance and certain celestial occurrences.

Bhārata celebrates the most festivals in the world; no culture has as many reasons to celebrate as we do. Each festival is unique in not just its significance but also in the style of enjoyment. Thus Dīpāvalī, Poṅgal, Holī, Gaṇeśa Caturtī, Navarātri, Oṇam, Bihu and many other festivals – each one distinct by itself – are celebrated either across the nation or in specific regions.

Festivals are meant to bring people together. This is true of our festivals as almost all our festivals are celebrated beyond the confines of the homes of individuals. Cooking together during Poṅgal, displays in pandals during Durga Pūja, processions during Gaṇeśa Caturtī, bursting crackers during Dīpāvalī, throwing colours during Holī and different other ways such as dancing, plays, singing, storytelling and so on for other festivals ensure that the members of the community participate in the celebrations. All these ways help individuals to break inhibitions and enjoy the festivals as part of the community.

Festivals create economic vibrance in the society. These are times when many small and seasonal businesses thrive. Flowers, fruits, clothes, grains and other food items, decorative items, sweets, handcrafted items of worship, crackers and so many other businesses see a sharp increase in sales during the festival season. Thus, festivals makes life more enjoyable for the people and their families who see this as an advantageous time for themselves.

Festivals help to inculcate and reinforce social values and responsibilities. These are times when charity of all kinds is done. Eatables, clothes, money and gifts are given generously. Opportunities are created for even the poor to celebrate and enjoy the spirit of the festival.

Festivals serve as reminders of dharma by their association with the higher powers. They serve as occasions to share paurāṇik and aitihāsik content through various artforms.

In Bhārata, very significantly, festivals are associated with astronomical occurrences. This means that festivals also calibrate the earth year. The pañcāṅgam – which is a carefully designed chronology scale based on the five different attributes of the moon on a day and time – is used to determine the dates of occurrence of the festivals. This means that the pañcāṅgam and our festivals are inseparable.

Reason and season are both connected to the festival. The foods we prepare, the fruits and flowers that we offer and the rituals we perform, all these are connected to the bounty of nature at that time of the year.

With colonial rule and the replacement of the pañcāṅgam with the Gregorian calendar as the mainstream standard to indicate the date, the practice of reading the pañcāṅgam diminished among the population. Down the generations, the astronomical significance attached to the festivals is largely forgotten. Apart from this, the interconnectedness between festivals also fails to be understood as the calendar is simply a set of serial numbers which have no other connection between them. Now, most people only understand festivals to fall on specific “dates” which carry no meaning for them otherwise.

Being aware of all the dimensions of festivals make the celebrations wholesome and extremely joyous. This degree of enjoyment of festivals is perhaps unique to Bhāratīya cultures.

The lack of understanding of significance due to the disconnect between the Gregorian calendar and our festivals, makes it convenient for unfriendly forces to strip our festivals of all relevance and create mischief. Today, we can see children being told to celebrate crackerless Deepavali and waterless Holi because the disconnect has crept in even among the parents’ and grandparents’ minds. This is harmful and would weaken our culture very deeply and irreparably if work is not done soon to remedy the situation.

Reading the pañcāṅgam must become mainstay for people to begin to comprehend the significance of our festivals. Some suggestions are –

i) Teach pañcāṅgam in a scientific way in schools.

ii) Schools can read out pañcāṅgam during the assembly.

iii) Guest lectures on the science of pañcāṅgam can be given in schools for teachers/students.

NOTE: The author has taken the liberty to collate points that came up during a mandal, add some more relevant content and write the article.

If we revert to the pañcāṅgam, there is much hope that people would, once again, be able to view the high levels of science that are part of our systems and traditions.

Jai Hind!